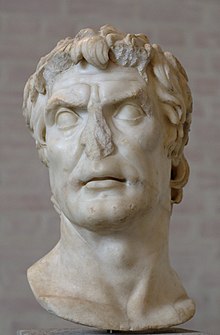

Quintus Sertorius

Quintus Sertorius | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Born | c. 126 BC | ||||||||

| Died | 73 or 72 BC (aged 53–54) Osca, Hispania | ||||||||

| Cause of death | Assassination (Stabbed to death) | ||||||||

| Known for | Rebellion in Hispania against the Roman Senate | ||||||||

| Office |

| ||||||||

| Military career | |||||||||

| Allegiance | Roman Republic Marius–Cinna faction | ||||||||

| Battles / wars | |||||||||

Quintus Sertorius (c. 126 BC[6] – 73 or 72 BC[7]) was a Roman general and statesman who led a large-scale rebellion against the Roman Senate on the Iberian Peninsula. Sertorius became the independent ruler of Hispania for most of a decade until his assassination.

Sertorius first became prominent during the Cimbrian War fighting under Gaius Marius, and then served Rome in the Social War. After Lucius Cornelius Sulla blocked Sertorius' attempt at the plebeian tribunate c. 88 BC, following Sulla's consulship, Sertorius joined with Cinna and Marius in the civil war of 87 BC. He led in the assault on Rome and restrained the reprisals that followed. During Cinna's repeated consulships he was elected praetor, likely in 85 or 84 BC. He criticised Gnaeus Papirius Carbo and other Marians' leadership of the anti-Sullan forces during the civil war with Sulla and was, late in the war, given command of Hispania.

In late 82 BC Sertorius was proscribed by Sulla and forced from his province. However, he soon returned in early 80 BC, taking in and leading many Marian and Cinnan exiles in a prolonged war, representing himself as a Roman proconsul resisting the Sullan regime at Rome. He gathered support from other Roman exiles and the native Iberian tribes – in part by using his tamed white fawn to claim he had divine favour – and employed irregular and guerrilla warfare to repeatedly defeat commanders sent from Rome to subdue him. Sertorius allied with Mithridates VI of Pontus and Cilician pirates in his struggle against the Roman government.

Sertorius successfully sustained his anti-Sullan resistance in Hispania for many years, despite substantial efforts to subdue him by the Sullan regime and its generals Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius and Pompey. After defeating Pompey in 76 BC at the Battle of Lauron however, he suffered numerous setbacks in later years. By 73 BC his allies had lost confidence in his leadership; his lieutenant Marcus Perperna Veiento assassinated him in late 73 or 72 BC.[6] His cause fell in defeat to Pompey shortly thereafter.[8] The Greek biographer and essayist Plutarch chose Sertorius as the focus of one of his biographies in Parallel Lives, where he was paired with Eumenes of Cardia, one of the post-Alexandrine Diadochi.

Early life and career

[edit]Sertorius was born in Nursia in Sabine territory around 126 BC.[9] The Sertorius family were of equestrian status. It appears that he did not have any noteworthy ancestors and was thus a novus homo (a "new man"), ie the first of his family to join the Senate.[10]

Sertorius' father died before he came of age and his mother, Rhea,[11] focused all her energies on raising her only son. She made sure he received the best education possible for a young man of his status. In return, according to Plutarch, he became excessively fond of his mother.[12] Having inherited his father's clients, like many other young rural aristocrats (domi nobiles), Sertorius sought to begin a political career and thus moved to Rome in his mid-to-late teens trying to make it big as an orator and jurist.[13]

His speaking style made a sufficiently negative impression on the young Cicero to merit a special mention in a later treatise on oratory:[14]

Of all the totally illiterate and crude orators, well, actually ranters, I ever knew – and I might as well add 'completely coarse and rustic' – the roughest and readiest were Q. Sertorius ...[15]

After his undistinguished career in Rome as a jurist and an orator, he entered the military.[16] Sertorius' first recorded campaign was under Quintus Servilius Caepio as a staff officer and ended at the Battle of Arausio in 105 BC, where he showed unusual courage. When the battle was lost, Sertorius escaped while wounded by swimming across the Rhone, apparently still with his weapons and armour.[17] This became a minor legend in antiquity, still remembered in the time of Ammian.[18]

Service under Gaius Marius

[edit]

Serving under Gaius Marius, sometime between the autumns of 104 and 102 BC, Sertorius spied on the Germanic tribes that had defeated Caepio, probably disguised as a Gaul.[19] Marius may have sought Sertorius (and other survivors of Arausio) out due to their experience fighting against the Germans, as he likely wanted information regarding enemy tactics and movements.[20] Sertorius probably did not know enough of the German languages to comprehend detailed information, but could report on their numbers and formations: "after seeing or hearing what was of importance", he returned to Marius.[21]

Sertorius became well-known and trusted by Marius during his service with him.[22] He almost certainly fought with his commander at the Battle of Aquae Sextiae (now Aix-en-Provence, France) in 102 BC and the Battle of Vercellae in 101 BC, in which the Teutones, Ambrones, and Cimbri were decisively defeated.[23]

Some scholars believe that Sertorius' tactics and strategies during his revolt in Hispania were substantially similar to Marius' and conclude that Sertorius' earlier service with Marius was an important learning experience.[24] What Sertorius did for the next three years is unclear, but he probably continued to serve in the military.[25] Sertorius eventually travelled to Hispania Citerior to serve its governor, Titus Didius, as military tribune in 97 BC.[26]

Pacification of Castulo

[edit]During his service, Sertorius was posted to the Roman-controlled Oretani (Iberian) town of Castulo. The local garrison had become hated by the natives for their lack of discipline and constant drinking, and Sertorius either arrived too late to stop their impropriety or was unable to.[27] The natives invited a neighbouring tribe to free the town of the garrison, and they successfully slaughtered many of the Roman soldiers. Sertorius managed to escape and gathered the other surviving soldiers, who still had their weapons.[28][27] He secured the unguarded exits of the town, and then led his men inside, killing all barbarian men of military age irrespective of participation in the revolt.[28] Once he learned some attackers had come from a neighbouring town, he had his men wear the armour of the slain natives and led them there. Probably arriving at dawn, the town opened the gates for Sertorius and his men, convinced they were their warriors returning with loot from the slain Roman garrison.[27] Sertorius then killed many of the towns' inhabitants and sold the rest into slavery.[28]

Later in Hispania during his revolt, Sertorius did not quarter his soldiers in native cities, "noting the stupidity of a policy which would cause rebellion in a hostile city, hostility in a neutral one, and corrupt the garrison into the bargain".[29] The incident at Castulo earned Sertorius considerable fame in Hispania and abroad, aiding his future political career. During his military tribunate Sertorius probably became familiar with the Iberian methods of war, namely guerrilla warfare, which he would later use to great effect in his revolt.[30]

Didius returned to Rome in the June of 93 BC to celebrate a triumph, but it is not known whether Sertorius immediately returned with him. As one of Didius' experienced officers, Sertorius may have remained in Hispania in 92 BC to continue subduing the Iberian tribes under Didius' successor, Gaius Valerius Flaccus.[31] Alternatively, Sertorius may have spent the year in Rome gathering support for his quaestorship; as a novus homo the necessary political maneuvering would have required time and effort.[32]

Social War and civil unrest

[edit]In 92 BC, upon his return from his military tribunate in Hispania, Sertorius was elected quaestor and assigned Cisalpine Gaul in the year 91.[33] His quaestorship was unusual in that he largely governed the province while the actual governor, perhaps Gaius Coelius Caldus, spent time across the Alps subduing remnants of the Cimbric invasion.[34] The same year, the Social War broke out, and Sertorius contributed by levying soldiers and obtaining weapons. He may have done more, though the existing sources do not record it. According to the historian Sallust:

Many successes were achieved under his [Sertorius] leadership, but these have not been recorded in history, firstly because of his humble birth and secondly because the historians were ill-disposed towards him.[35]

His quaestorship may have been prorogued into 90 BC.[36] Between 90–89 BC he almost certainly led as a commander and fought, along with providing men and materiel to the southern theatres of the war.[37] He served under a series of commanders, probably Marius and Lucius Porcius Cato,[38] most certainly under Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo.[39] A wound sustained during the conflict cost him the use of one of his eyes.

Sertorius used his wounds as personal propaganda. Being scarred in the face had its advantages. "Other men, he used to say, could not always carry about them the evidence of their heroic achievements. Their tokens, wreaths and spears of honour must at some times be set aside. His proof of valour remained with him at all times".[40]

Upon his return to Rome he apparently enjoyed the reputation of a war hero.[41] Sertorius then ran for tribune of the Plebs in 89 or 88 BC, but Lucius Cornelius Sulla thwarted his efforts, causing Sertorius to oppose Sulla. Sulla's reasons for doing so are unclear. It may have originated in a personal quarrel since both men served under Marius earlier in their careers.[42] It is also equally possible Sulla (and by extension the optimates, who he was closely tied to through marriage with Caecilia Metella and opposition to Marius) were uncertain about what manner of tribune Sertorius would be, and not being able to rely on his obedience led to their opposition.[42] Knowing Sertorius was popular with the common people and associated with Marius may have been enough to thwart his ambitions. In any case, Sertorius was a senator by 87 BC,[43] likely adlected due to his earlier quaestorship[citation needed].

Sulla's consulship and the bellum Octavianum

[edit]In 88 BC, after Publius Sulpicius Rufus and Marius supplanted his eastern command, Sulla marched his legions on Rome and took the capital. He took revenge on his enemies and forced Marius into exile, then left Italy to fight the First Mithridatic War against Mithridates VI of Pontus. Sulla did not harm Sertorius, probably because he had not participated in Marius and Rufus' actions. After Sulla left, violence erupted between Sullan loyalists, led by the consul Gnaeus Octavius, and the Marians, led by the consul Lucius Cornelius Cinna. Cinna, as "the enemy of his enemy [Sulla]" and "not so much... an old ally of Marius as the newly emerging leader of those who disapproved of Sulla's coup" represented a re-emergence of Sertorius' political fortunes.[44][45] As a result of this, and remembering Sulla's opposition when he ran for tribune, Sertorius declared for the Marian faction.[46][47]

Cinna was driven from Rome in 87 BC during the Bellum Octavianum. Sertorius, as one of his allies, aided him in recruiting ex-legionaries and drumming up enough support to enable Cinna to march on Rome. When Marius returned from exile in Africa to aid the Marian cause, Sertorius opposed granting him any command either out of fear his position would be diminished, or because he feared Marius' vindictiveness and what he would do when Rome was retaken.[48] Sertorius advised not to trust Marius, and although he greatly disliked Marius by then, he consented to Marius' return upon understanding that Marius came at Cinna's request and not of his own accord.

Oh, really? Here I was thinking that Marius had decided for himself to come to Italy, and so I was trying to decide what good it would do. But it turns out there's nothing to discuss. Since after all, you invited him, then you have to receive and employ him. There's no question about it.[49]

In October of 87 BC, Cinna marched on Rome. During the siege, Sertorius commanded one of Cinna's divisions stationed at the Colline Gate and fought an inconclusive battle with troops commanded by Pompeius Strabo. Sertorius and Marius also bridged the Tiber to prevent supply from reaching the city by river.[50] After Octavius surrendered Rome to the forces of Marius, Cinna, and Sertorius, Sertorius abstained from the proscriptions and killings his fellow commanders engaged in. Sertorius went so far as to rebuke Marius and move Cinna to moderation.[51] After Marius' death he, probably with Cinna's approval, annihilated Marius' slave army which was still terrorizing Rome.[52]

Civil war against Sulla

[edit]The years 87–84 BC are often described as spent "waiting for Sulla"[53] and what exactly Sertorius did while Cinna controlled Rome is unclear. He was not sent with Gaius Flavius Fimbria and Lucius Valerius Flaccus east for the First Mithridatic War. Sertorius certainly served in the government during this time; Cinna may have utilized his skill as a soldier and popularity with the common people to quell any remnants of revolt and stabilize Italy, thereby consolidating his power and that of the Marian government. He probably also helped train and levy soldiers for Sulla's inevitable return. Marius died in January 86 BC; eventually, Cinna himself was murdered in 84 BC, lynched by his own troops. It is probable that Sertorius became praetor in 85 or 84 BC.[54]

On Sulla's return from the East in 83 BC a civil war broke out. Sertorius, as a praetor, steadied the Marian leadership and was among the men chosen to command the anti-Sullan forces against him.[55] When the consul Scipio Asiaticus marched against Sulla, Sertorius was part of his staff. Sulla arrived in Campania and found the other consul, Gaius Norbanus, blocking the road to Capua. At the Battle of Mount Tifata Sulla inflicted a crushing defeat on Norbanus, with Norbanus losing thousands of men.

The beaten Norbanus withdrew with the remnants of his army to Capua. Sulla was stopped in his pursuit by Scipio's advance. However, Scipio was unwilling to risk a battle and started negotiations under a flag of truce. Sulla's motives in agreeing to the negotiations were not sincere,[56][57] in that he likely agreed intending to make Scipio's already disaffected army more likely to defect to him. Sertorius was present at the talks between the commanders, and advocated against letting Sulla's troops fraternize with Scipio's;[58] he did not trust Sulla and advised Scipio to force a decisive action. Instead, he was sent to Norbanus to explain that an armistice was in force and negotiations were underway.

Sertorius made a detour along his way and captured the town of Suessa Aurunca which had gone over to Sulla.[59] When Sulla complained to Scipio about this breach of trust by Sertorius, Scipio gave back his hostages as a sign of good faith. Disappointed by the behavior of their commander and unwilling to fight Sulla's battle-hardened veterans, Scipio's troops defected en masse. Scipio and his son were captured by Sulla, who released them after extracting a promise that they would never again fight against him or rejoin Cinna's successor Carbo.[60]

Sertorius motives for seizing Suessa are debated. It is possible the city defected to Sulla during the armistice (perceiving Scipio's negotiations as a sign of weakness), and thus Sertorius, en route to Norbanus, conquered the town to restore the status quo.[61][62] It is also possible Sertorius, who distrusted Sulla and doubted the judgement of Scipio, conquered the city intending to force an end to negotiations. Spann believes that calling Sertorius' seizure of Suessa a "foolish action" is not wholly unjustified, but argues against trusting Appian's account (the only one that survives, based on Sulla's memoirs) which states Sertorius' capture of Suessa as being the main cause of negotiations ending and the defection of the Marian army.[63] So Konrad: "the loss of the Consul's [Scipio's] army was not caused by the seizure of Suessa".[56]

After Suessa, Sertorius departed to Etruria where he raised yet another army, some 40 cohorts, as the Etruscans, having gained their Roman citizenship through the Marian regime, were fearful of a Sullan victory.[64] In 82 BC, Marius' son, Gaius Marius the Younger, became consul without having held the offices that a candidate for the consulship should have held, and at the unconstitutional age of 27. Sertorius, who probably qualified for the office, objected but his opinion was ignored.[65] Following this appointment, Sertorius returned to Rome and castigated the Marian leadership for their lack of action in combatting Sulla, pointed out Sulla's bravery, and stated his belief that unless met directly soon Sulla would inevitably destroy them. Plutarch sums up the events:

Cinna was murdered and against the wishes of Sertorius, and against the law, the younger Marius took the consulship while such [ineffectual] men as Carbo, Norbanus, and Scipio had no success in stopping Sulla's advance on Rome, so the Marian cause was being ruined and lost; cowardice and weakness by the generals played its part, and treachery did the rest, and there was no reason why Sertorius should stay to watch things going from bad to worse through the inferior judgement of men with superior power.[66]

Governor of Hispania and fugitive

[edit]

By late 83 or early 82 BC, having fallen out with the new Marian leadership, Sertorius was sent to Hispania as proconsul,[67] "no doubt by mutual agreement".[68] Sertorius may have been intended to go to Hispania even before Sulla's Civil War in order to relieve command of the two Spanish provinces (Hispania Ulterior and Hispania Citerior) from their governor, Gaius Valerius Flaccus, due to his doubtful loyalty to the Marian regime.[69]

When Sertorius marched through the Pyrenees mountain range he ran into severe weather and a mountain tribe that demanded a tribute for allowing his passage. His companions claimed it was an outrage; but Sertorius paid the tribe and commented that he was buying himself time, and that if a man had a lot to do, nothing is more precious than time.

Flaccus, the governor of the two Spanish provinces, did not recognize his authority, but Sertorius had an army at his back and used it to assume control. He did not meet with significant resistance in his first seizure of Hispania.[70] Sertorius persuaded the local chieftains to accept him as the new governor and endeared himself to the general population by cutting taxes, and then began to construct ships and levy soldiers in preparation for the armies he expected to be sent after him by Sulla. After gaining control of both provinces Sertorius sent an army, under Julius (possibly Livius)[71] Salinator, to fortify the pass through the Pyrenees.

During his occupation of Hispania Sertorius collected news of the war in Italy. Likely from refugees and Marian exiles fleeing Sulla's veteran legions, by December of 82 BC[72] he had heard of Sulla's victory over the Marians in various battles, his second capture of Rome, and the Sullan proscriptions. Sertorius learned that he was one of the foremost among the proscribed, among the first names listed.[73][74]

By 81 BC all other significant Marian leaders were dead, and Sertorius' Spain had become a priority for the Sullan government. Sulla's forces, probably three or four legions[76] under the command of Gaius Annius Luscus, departed for Hispania early in 81 or very late in 82 BC, but were unable to break through the Pyrenees until Salinator was assassinated by P. Calpurnius Lanarius, one of his subordinates, who defected to the Sullans. Annius then marched into Hispania.

Flight from Hispania to Tangier

[edit]Unable to convince the Spanish tribes to fight for him, Sertorius was seriously outnumbered and he abandoned his provinces. He fled to Nova Carthago and with 3,000 of his most loyal followers set sail to Mauritania, perhaps attempting some sort of attack on the coastal cities to keep his forces together, but was driven off by the locals. He then fell in with a band of Cilician pirates who were pillaging the Spanish coast. Together they attacked and took Pityussa, the most southerly of the Balearic Islands, which they started using as a base. When this was reported to Annius, he sent a fleet of warships and almost a full legion to drive Sertorius and his pirate allies from the Balearics. Sertorius engaged this superior fleet in a naval battle to avoid allowing them to disembark,[77] but adverse winds broke most of his lighter ships, and he eventually fled the islands.

Sertorius heard of, and had a genuine interest in the Isles of the Blessed, ascribing the isles to the Celto-Hispanian belief of an afterlife in the western ocean and learning more for his own political purposes.[78] While he was idle Sertorius' pirate allies defected and went to Africa to help install the tyrant Ascalis on the throne of Tingis. Sertorius followed them to Africa in the fall of 81 or the spring of 80 BC, rallied the locals in the vicinity of Tingis, and defeated Ascalis' men and the pirates in battle. After gaining control over Tingis, Sertorius defeated and killed the general Vibius Paciaecus and his army, who was probably sent by Annius against him.[79] Paciaecus' defeated army then joined Sertorius.[80]

Local legend had it that Antaeus, the son of Poseidon and Gaia, and the husband of Tinge who gave name to Tingis, was buried in Mauritania. Sertorius had the tomb excavated for he wanted to see the body of Antaeus which was reported to be sixty cubits[81] in size. According to Plutarch, Sertorius was dumbfounded by what he saw and after performing a sacrifice, he filled the tomb up again, and thereafter was among those promoting its traditions and honours.[82]

Sertorius remained in Tangier for some time.[83] News of his success against Ascalis spread, and won Sertorius fame among the people of Hispania, particularly that of the Lusitanians in the west, whom Roman generals and proconsuls of Sulla's party had plundered and oppressed. The Lusitanians, being threatened by a Sullan governor again, asked Sertorius to be their war leader.

It is likely they were influenced by Sertorius' tenure as governor being far gentler than his predecessors, who often extracted very high taxes and warred against tribes arbitrarily for glory and plunder, neither of which Sertorius had done.[84] The Lusitanians were also implored by Sertorius' "friends in Spain",[85] likely Roman exiles who knew Sertorius, but were unable to flee with him when Annius retook Hispania and had consequently taken refuge in Lusitania.[86] Sertorius did not lead the Lusitanians in a 'war of liberation' from the Roman Republic however; instead, the Lusitanians, hoping for his milder administration to return, offered their support for him to revive the defeated Marian cause with Hispania as his base.[87][88]

While considering the offer, Sertorius learned of his mother's death in Italy and "almost died of grief", lying in his tent, unable to speak for a week.[89] With the aid of his companions, Sertorius was eventually able to leave his tent, decided to accept the Lusitanian offer, and prepared his army and fleet to return to Hispania.

Sertorian War

[edit]

Sertorius crossed the strait at Gibraltar at Tingis in 80 BC, landing at Baelo near the Pillars of Hercules in the summer or fall of the year.[90] A small fleet under an Aurelius Cotta (specific name not known) from the coastal town of Mellaria failed to stop him.[91] After being reinforced by the Lusitanians he marched on Lucius Fufidius, propraetor of Hispania Ulterior,[92] and defeated him at the Battle of the Baetis River, consolidating control over the province.[93][94] News of Sertorius' victory spread throughout Hispania Ulterior, including a rumour that his army included fifty thousand cannibals.[95]

Lusitania and Lacobriga

[edit]The Senate learned that Sertorius had returned to Hispania, and as a result sent Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius, an experienced Sullan general, with a proconsular command by the Senate specifically to defeat and drive him from Hispania Ulterior.[96] Metellus would be Sertorius' main antagonist between 80–77 BC.

Prior to Metellus' arrival, Marcus Domitius Calvinus, proconsul in Hispania Citerior,[97] marched against Sertorius but was defeated by Lucius Hirtuleius, Sertorius' legate. Sertorius, who referred to Metellus as "the old woman", employed guerrilla warfare effectively and outmaneuvered Metellus through rapid and relentless campaigning.[98] Sertorius also defeated and killed Lucius Thorius Balbus, Metellus' legate.

Although initially outnumbered, Sertorius' repeated victories, along with his "uncharacteristically humane" administration impressed the native warriors, many of whom joined his cause.[99] His character, in that he treated the natives as allies rather than subjects, may have also played a role.[100] Sertorius organized the natives into an army and adjoined them to his core Roman forces, commanding them under Roman officers.[101] The natives are said to have called Sertorius the "new Hannibal" whom he resembled physically (having one eye) and, they believed, in military skill.[102]

Although he was strict and severe with his soldiers, Sertorius was considerate to the natives, and made their burdens light despite financial strain in his war effort.[103] This was likely partially pragmatic, as Sertorius had to retain the goodwill of the native Iberians if he had any chance of winning the war. Sertorius' most famous strategy to this end was his white fawn, a present from one of the natives that he claimed communicated to him the advice of the goddess Diana, who had been syncretized with a native Iberian deity.[104]

Spanus, one of the commoners who lived in the country, came across a doe trying to escape from hunters. The doe fled faster than he could pursue, but the animal had newly given birth. He [Spanus] was struck by the unusual colour of the fawn, for it was pure white. He pursued and caught it.[105]

The Iberians were greatly impressed by the fawn, who was calm in Sertorius' military camp and affectionate with him, and saw Sertorius as a divinely inspired leader.[100] Sertorius would obscure information from military reports, claim Diana had told him of said information through the fawn in his dreams, and then act accordingly to further this belief.[106] White animals were perceived as having oracular qualities among Germanic peoples, and in Hispania itself there existed a stag cult of funerary and oracular nature; this cult was most popular in western Hispania and Lusitania, where Sertorius drew his most fervent followers.[107] As a result of all of these factors, Sertorius' power and army grew exponentially in 80 and 79 BC.[108]

Sertorius successfully gained control over both Hispanian provinces with the aid of Hirtuleius in 79 BC despite Metellus' efforts. From 78 BC onward Metellus campaigned against Sertorian cities, but Sertorius thwarted his invasions into Lusitania and Ulterior. When Sertorius learned of Metellus' intention to siege Lacobriga, Sertorius supplied the city in response, and then prepared to meet Metellus there. When Metellus arrived and sent out foragers, Sertorius ambushed them and killed many, forcing Metellus to leave, unsuccessful. In 77 BC, Sertorius focused his attention on subduing Iberian tribes who had not yet accepted his authority in the interior. Metellus did not extensively campaign against Sertorius in the year due to the revolt in Rome of the consul Marcus Aemilius Lepidus (father of the triumvir). At some point during these years, Sertorius challenged Metellus to single combat, and when Metellus declined, his soldiers mocked him.

Sertorius' made the Iberians an organized army through Roman formations and signals.[110] He encouraged them to decorate their armaments with precious metals, and thus more likely to retain their equipment between engagements. Many native Iberians pledged themselves to him, serving as bodyguards who would take their own lives if he perished.

Famously, while organizing his armies, the natives under Sertorius' command wanted to take on the Roman legions head-on. Unable to convince them otherwise, he allowed the natives to do so in a minor engagement. Afterward, he had two horses brought in front of them, one strong, the other weak. He ordered an old man to pull hairs from the strong horses' tail one by one, and a strong youth to pull on the weak horses' tail all at once; the old man completed his task, while the youth failed. Sertorius then explained that the Roman army was similar to the horse tail, in that it could be defeated if attacked piece by piece, but if taken all at once victory was impossible.[111][112]

Contrebia and Lauron

[edit]

In the summer of that year, with Lepidus' revolt having ended, the Roman Senate recognized a greater force was needed to defeat Sertorius, as to this point all Sullan generals had been defeated or killed and Metellus had proven to be no match for him.[96][59] Both sitting consuls, however, refused to command the war against Sertorius.[114] The Senate resorted to giving an extraordinary command to Pompey to crush Sertorius' rebellion.[115] Soon after, probably in late 77 BC, Sertorius was joined by Marcus Perperna Veiento, with a following of Roman and Italian aristocrats and a sizeable Roman-style army of fifty-three cohorts.[116] With this army Sertorius was able to meet the Roman commanders in open field engagements instead of only guerrilla warfare.

Sertorius successfully sieged the native city of Contrebia in that year. Afterward, he called together representatives of the Iberian tribes, thanked them for their aid in providing arms for his troops, discussed the progress of the war and the advantages they would have if he was victorious, and then dismissed them.[117]

By the 76 BC campaigning season, Pompey had recruited a large army, some 30,000 infantry and 1,000 cavalry from his father and Sulla's veterans, its size being evidence of the threat posed by Sertorius to the Sullan Senate.[118] His arrival in Hispania stirred up rebellious sentiments against Sertorius in the peninsula, due to Pompey's reputation as a skilled general. Sertorius paid close attention to Pompey's movements despite his open contempt toward the younger general, who he called "Sulla's pupil".[119] Sertorius was now at the height of his power, as near all of Iberia was under his control and he had several large armies throughout the peninsula with which to combat the Roman generals.[120]

Sertorius, apparently, did not intend to march on Pompey or expect him to offer battle.[117] He began the year with minor raids into the lands of the Berones and Autricones, presumably wanting to set a reliable headquarters in northern Hispania.[121] When Pompey marched toward Valentia, Sertorius rapidly moved south and blockaded the strategic city of Lauron in Citerior, which had recently allied itself to Pompey. Sertorius besieged the city, likely hoping to pull Pompey from Valentia by attacking a new ally of his.

In response, Pompey made for Lauron, and saw Sertorius encamped there already, beginning the Battle of Lauron. Sertorius remarked that he would give a lesson to Pompey: that a general must look behind him rather than in front of him.[122] Sertorius outmaneuvered Pompey during the battle, forcing him to stay in place by threatening an attack from the rear, then killed his foragers and a Pompeian legion sent to relieve the foragers. When Pompey tried to form up his entire army to save his forces, Sertorius led out his own army. Knowing he would be outflanked if he gave battle, Pompey desisted, and a third of his army was slaughtered. Sertorius let the native Lauronians go and burned down the city. He then executed an entire Roman cohort due to their attempts to plunder and ravage the Lauronians after he gave orders that they were to be unharmed.

Sertorius, in his efforts to build a stable powerbase in Hispania, is said to have established a Senate of three hundred members drawn from Roman emigrants in Iberia.[123] He probably did not start calling it a Senate, nor did it contain a significant number of senators, until the arrival of Perperna and the Marian/Lepidan exiles in 77 BC.[124] Whether the title of Senate was given to this body because it was a "government in exile" or innately due to the dignitas of its members is not known.[125] It included many men, possibly one hundred or more, who were genuine senators but had fled Rome.[126] Sertorius probably rose men of equestrian rank and other young nobles to his Senate to swell its numbers, and personally appointed proquaestors and propraetors; some men (such as Marcus Marius) apparently even advanced offices in his administration.[127] How often Sertorius convened his Senate aside from the treaty he formed with Mithridates VI, and indeed whether he had the power to do so regularly, is uncertain.[128] Though the quality of the Sertorian Senate deteriorated as Sertorius' war effort failed,[127] the body was numerous and powerful enough, for a time, to challenge the authority of the Sullan Senate.[129]

For the children of the chief native families Sertorius provided a school at Osca, his capital city, where they received a Roman education and even adopted the dress and education of Roman youths; Sertorius held exams for the children, distributed prizes, and assured them and their fathers they would eventually hold some positions of power.[130] This followed the Roman practice of taking hostages. Sertorius may have promised to grant these children, along with their families, Roman citizenship.[131]

Sucro and Saguntum

[edit]In 75 BC, Perperna and Herennius were defeated at the Battle of Valentia by Pompey.[132] Hearing this, Sertorius left the command against Metellus with Hirtuleius and marched his army to meet Pompey. Metellus defeated Hirtuleius at the Battle of Italica,[133][134] so Sertorius sent Perperna at the head of a large army to block Metellus from coming to Pompey's aid and engaged Pompey, who, for whatever reason, chose to accept the offer of battle rather than wait for his ally, beginning the Battle of Sucro late in the day.[135]

Each general took the right flank; Pompey faced a Sertorian legate, while Sertorius faced Lucius Afranius. When Sertorius saw his left wing falling to Pompey, he rallied them and led a counterattack which shattered the Pompeian right, nearly capturing Pompey himself.[136] Afranius, however, had broken the Sertorian right and was plundering their camp; Sertorius rode over and forced Afranius to depart back to Pompey. Both armies drew up again the next day, but Sertorius then heard Metellus had defeated Perperna and was now marching to aid Pompey.[137] Unwilling to fight two armies who would outnumber him if joined, Sertorius decamped, bitterly commenting:

Now if the old woman had not made an appearance, I'd have thrashed the boy and packed him off to Rome.[138]

Sertorius negotiated with King Mithridates VI of Pontus during his war, likely in the winter of 75 BC. Mithridates wanted Roman confirmation of his occupation of the Roman Province of Asia, after relinquishing control of it to Sulla in the First Mithridatic War, along with the Kingdoms of Bithynia and Cappadocia. Sertorius assembled his Senate to discuss the issue, and decided that Mithridates could get Bithynia and Cappadocia (and possibly Paphlaglonia and Galatia as well) as they were kingdoms that "had nothing to do with the Romans".[139] But Asia, being a Roman province, would not be allowed to be his again. Mithridates accepted these terms and sent 3,000 talents of gold and forty ships to Sertorius.

Sertorius was eventually forced by his native troops to give battle against Metellus and Pompey, likely when Metellus marched on the Celtiberian town of Segontia. The coming Battle of Saguntum was the last pitched battle Sertorius fought, the largest battle of the war, and probably one he had not wanted in the first place. The fighting lasted from noon until night-time and resulted in the deaths of Gaius Memmius and Hirtuleius. Though Sertorius defeated Pompey on the wing, Metellus again defeated Perperna. The battle ultimately ended in a draw, with heavy losses for both sides.

Following the battle Sertorius disbanded his army, telling them to break up and reassemble at a later location rather than organizing a concerted retreat, for fear of Metellus' pursuit.[140] This was common for Sertorius, who "wandered about alone, and often took field again with an army... like a winter torrent, suddenly swollen".[141]

Clunia and the final years

[edit]After the battle Sertorius reverted to guerrilla warfare, having lost the heavy infantry Perperna had lent to his cause which enabled him to match the Sullan legions in the field. He retired to a strong fortress town in the mountains called Clunia. Pompey and Metellus rushed to besiege him, and during the siege, Sertorius made many sallies against them, inflicting heavy casualties.[142] Sertorius convinced Metellus and Pompey that he intended to remain besieged, and eventually broke through their lines, rejoined with a fresh Sertorian army, and resumed the war.[143]

The two Roman generals had pursued Sertorius into unfriendly lands and thus Sertorius regained the initiative. For the rest of the year he resumed a guerrilla campaign against them, eventually forcing Metellus and Pompey to winter out of Sertorian-aligned land due to lack of resources.[141] During that winter, Pompey wrote to the Senate for reinforcements and funds, without which, he said, he and Metellus would be driven from Hispania. Despite being weakened, Sertorius was still perceived as a threat, as in Rome it was apparently said that he would return to Italy before Pompey did.[143] The Senate capitulated to Pompey's demands; funds and men (two legions) were found with effort and sent to the Roman generals.

With the men and materiel reinforcements from Pompey's letter, in 74–73 BC, Pompey and Metellus gained the upper hand. The two Roman generals began slowly grinding down Sertorius' rebellion via attritional warfare. Sertorius lacked the men to meet them in open combat, though he continued to harry them with guerrilla warfare. Mass defections to the Roman generals began, and Sertorius responded to this with harshness and punishments.[144] Sertorius won some victories here and there, but it was by now clear he could not achieve complete victory.[145] The Roman generals continued to occupy strongholds that were once under his control, and Sertorius' support among the Iberian tribes faltered as discontent among his Roman staff rose.

Sertorius was in league with the Cilician Pirates, who had bases and fleets all around the Mediterranean.[146] Near the end of his war he was also in communication with the insurgent slaves of Spartacus in Italy, who were openly in revolt against Rome. But due to jealousies and fears among his high-ranking Roman officers a conspiracy was beginning to take form.[144]

Conspiracy and death

[edit]Metellus, seeing that the key to victory was removing Sertorius, had made his pitch toward the Romans still with Sertorius sometime between 79 and 74 BC, likely later rather than earlier: "Should any Roman kill Sertorius he would be given a hundred talents of silver and twenty-thousand iugera of land. If he was an exile he would be free to return to Rome".[147][148] This "exorbitant" proposed payment for Sertorius' assassination equated to about fifty times the sum granted for the murder of a regular proscribed Roman.[149]

Metellus' proclamation eventually turned Sertorius paranoid, and he started distrusting his Roman retinue, including his Roman bodyguard, which he exchanged for a Spanish one.[150] This was deeply unpopular among his Roman followers. From late 74 BC onward, the once mild and just Sertorius had become paranoid, irritable, and exceedingly cruel to his subordinates, descending into alcoholism and debauchery.[151] Plutarch writes that "as his cause grew hopeless, he became harsh toward those who did him wrong".[152] Despite Spann's belief that reports of Sertorius' tyranny may be exaggerated or wholly false, Konrad argues that "only too well do they fit the pattern of the charismatic leader forsaken by good luck", and that their common presence across ancient sources, among other reasons, tells against their fabrication.[153]

By the autumn of 73 BC, the Roman aristocrats who comprised the higher classes of his domain were discontent with Sertorius. They had grown jealous of his power, resentful from his paranoia and cruelty, and could now see that victory was growing impossible. Sertorius' return to guerrilla warfare in 74 BC had worsened this by placing the Iberians in his retinue in more prominent positions than his Roman staff.[154] Perperna, aspiring to take Sertorius' place, encouraged the discontent of Sertorius' top Roman staff for his own ends, and led the conspiracy against him.[155] The conspirators took to damaging Sertorius by oppressing the local Iberian tribes in his name.[144] This stirred discontent and revolt in the tribes, resulting in a cycle of oppression, with Sertorius uncertain as to the cause. Sertorius executed and sold many of the Oscan schoolchildren into slavery as a result of these native revolts.

Assassination

[edit]

One of the conspirators, Manlius, told one of his lovers about the plot against Sertorius' life. This man then told another conspirator, Aufidius, who told Perperna. Perperna, accordingly, urged on by the "sharpness of their crisis and of their peril" took action.[156] He told Sertorius of a supposed victory over the Roman generals. Sertorius was elated by this news, while Perperna suggested a banquet and with effort persuaded Sertorius to attend in order to separate him from his bodyguards.

The banquet took place at Osca, Sertorius' capital, in late 73 or early 72 BC. The conspirators included many of Sertorius' top staff, such as Marcus Antonius, Lucius Fabius Hispaniensis, Gaius Octavius Graecinus, Gaius Tarquitius Priscus (all proscribed senators), Aufidius, Manlius, and Perperna himself. Sertorius' scribes, Versius and Maecenas, may have been involved since they were in perfect positions to forge evidence of Perperna's supposed victory.[157] Sertorius' loyal Spanish bodyguards were made drunk and kept outside of the banquet hall.[158]

Although Appian's description of Sertorius' debauchery may be exaggerated, Konrad believes he was certainly drunk at the banquet.[159] Plutarch reports that any festivities Sertorius was invited to were apparently very proper, but this banquet was purposely indecent, "with the hope of angering Sertorius".[156] Why the assassins would have sought to goad Sertorius is unclear, given an agitated man would be harder to kill than an unsuspecting one. Sertorius, either out of disgust or due to his inebriation, threw himself back on the couch he was resting on.[160] Perperna then gave the signal to his fellow conspirators by dropping his goblet on the floor, and they attacked. Antonius slashed at Sertorius, but he turned away from the blow and would have risen if Antonius did not hold him down.[156] The others stabbed him until he was dead.

Aftermath

[edit]Upon learning of the death of Sertorius, some of his Iberian allies sent ambassadors to Pompey or Metellus and made peace. Most simply went home. Iberian support for the Sertorian cause deteriorated rapidly after Sertorius' death: the Lusitanians in particular (who were among Sertorius' greatest partisans) were infuriated by his assassination.[161] What happened to Sertorius' white doe and his body is not known.

Perperna assumed control of the deteriorating rebel army after Sertorius' assassination. He was only able to avoid violence from the soldiers and natives by giving gifts, releasing prisoners and hostages, and by executing several leading Sertorians, including his own nephew.[162] To make matters worse, Sertorius' will named Perperna his chief beneficiary.[163] Already disgraced as the man who had slain his commander, the man who had given him sanctuary, Perperna was now also revealed to have killed his main benefactor and friend. Sertorius' death also led many to remember his virtues, and not his recent despotism.

People are generally less angry with those who have died, and when they no longer see him alive before them they tend to dwell tenderly on his virtues. So it was with Sertorius. Anger against him suddenly turned to affection and the soldiers clamorously rose up in protest against Perperna.[163]

After Sertorius' death his independent "Roman" Republic crumbled with the renewed onslaught of Pompey and Metellus. Metellus, who "considered it no longer a difficult task for Pompey alone to vanquish Perpenna" left for other parts of Hispania.[164] Pompey subsequently crushed Perperna's army and killed the rest of Sertorius' assassins and top Roman staff due to their proscribed status. Some fled to Africa and may have ended in the service of the mercenary Publius Sittius.[165] The only known survivor, Aufidius, "came to old age in a barbarian village, a poor and hated man".[166] Other Sertorian officers and soldiers (who were not proscribed, only hostes publici, or 'public enemies') were well treated by Pompey once they surrendered.[167]

Several Sertorian cities refused to surrender after the assassination of Sertorius, and Pompey remained in Hispania for some years pacifying these remaining holdouts. Most famously, the city of Calagurris resorted to cannibalism rather than submitting to the Roman siege, but was eventually taken by forces under Lucius Afranius.[168][169] The two victorious generals, each desiring a triumph, wanted the war to be considered foreign rather than civil.[170] When Pompey crossed the Pyrenees to return to Rome in 71 BC, he erected a monument to his victory speaking of the more than eight hundred towns he subjugated. The monument lacked any mention of Sertorius.[171]

During Gaius Julius Caesar's Gallic Wars, when his lieutenant Publius Licinius Crassus was conquering Aquitania in 56 BC, the Gauls sent ambassadors to many surrounding tribes for help, including Iberians from Hispania Citerior.[172] These Iberians were led by veterans who had fought with Sertorius during his war and had learned Roman military tactics from him; they showed "disconcerting proficiency in fighting Romans".[173] They picked prime positions for camps, conducted raids on supply lines, and did not overextend themselves.[172] Crassus eventually defeated these Sertorian veterans.

Legacy

[edit]Generalship and character

[edit]Ancient sources generally concede Sertorius was a great military leader (magnus dux), and note his proficiency in warfare.[174] Appian (who was hostile to Sertorius)[175] states his belief that despite his descent into debauchery and paranoia, "if Sertorius had lived longer the war would not have ended so soon or so easily".[164]

Frontinus recorded many of Sertorius' military tactics in his Stratagemata, with only a few Roman generals exceeding him.[176] Konrad notes that Sertorius proving "an instant master of the art" of guerrilla warfare is remarkable, given he was a Roman and probably did not train the skill.[30] Spann, more analytically, agrees Sertorius was a skilled tactician and guerrilla warrior, but criticizes his cautious strategy during the war, which led to his eventual defeat by Pompey.[177] Pliny's remark regarding Sertorius possibly winning the Grass Crown, tied sometimes to the Castulo incident in his early career, is refuted by scholars.[28][178]

During the Sullan Proscriptions, Sertorius was "especially feared"[73] and his war was not seen as a foregone conclusion while it was occurring. Some modern sources believe Sertorius was a traitor to Rome for his war against the Sullan Senate, cooperation with native Iberians against Roman armies, and alliance with Mithridates; others believe he was a true patriot of a defeated regime.[47] While ancient historians scorn Sertorius' cruelty and the "savage and prodigal" man he became late in his war, others admire his "great, but ill-starred, valour".[179] Livy appears to have viewed Sertorius not as "an Iberianized robber baron" but "a great Roman whose life went all wrong".[180] Similarly, Konrad believes Plutarch conceived the Life of Sertorius as the character study of "a gifted yet imperfect man struggling against an unkind fate, to no avail".[181]

No busts or coinage depicting Sertorius have survived. Despite Valerius Maximus reporting the presence of a wife in Italy,[182] there is no evidence of Sertorius having had any children.

Many commentators described Sertorius' life as a tragedy.[183] Plutarch wrote that "He [Sertorius] was more continent than Philip, more faithful to his friends than Antigonus, and more merciful to his enemies than Hannibal; and that for prudence and judgment he gave place to none of them, but in fortune was inferior to them all".[184] Gruen writes that "only the divisive contests of civil war forced him to end his life as a declared outlaw rather than an esteemed senator".[185] Spann concluded, "Sertorius' talents were wasted, his life lost, in an inglorious struggle he did not want, could not win, and could not escape".[186]

Impact on Pompey

[edit]Modern accounts that do not directly deal with Sertorius largely describe him and his war in terms of its impact on the Roman state, and his influence on the career of Pompey the Great. Leach calls Sertorius one of Pompey's "most brilliant adversaries",[189] and Collins refers to him as an "eccentric genius of guerrilla warfare".[190] Goldsworthy notes that Sertorius taught Pompey several "sharp lessons";[191] Pompey himself, in his letter to the Senate preserved by Sallust, purportedly wrote (describing the events of 76 BC) of how he weathered the first attack of the "triumphant Sertorius" and "spent the winter in camp amid the most savage of foes".[192]

Pompey's highly irregular career was initiated by the aftermath of the civil wars of Sulla and Marius, but it was the strong military threat Sertorius posed which necessitated his extraordinary, illegal, effectively proconsular command and thereby deteriorated the Senate's control over the Roman army.[193] Catherine Steel notes that Pompey's defeat of Sertorius, which solidified Pompey's extraordinary position in the state, "created its own set of problems".[59] Spann agrees, suggesting that Sertorius' central legacy was that his revolt "decisively transformed 'Sulla's Pupil' into Pompeius Magnus", whose prominence was to play a role in influencing yet further civil wars.[194]

Political legacy and motives

[edit]Sertorius' motives cannot really be known, though evidence suggests he saw himself fighting for the survival and re-enfranchisement of those disinherited and proscribed after Sulla's victory in 82 BC (including himself, who, like the rest, had no prospects in Sulla's republic).[96][195] Plutarch reports that Sertorius himself repeatedly sought terms with Metellus and Pompey to return to Rome (after a victory in the field), telling them he would rather "live in Rome as her meanest citizen rather than to live in exile from his country and be called supreme ruler of all the rest of the world together".[196] Katz believes this wish for a negotiated settlement may, in part, explain Sertorius' cautious strategy throughout his war.[197]

To the proscribed, Sertorius represented a chance for re-emergence in Roman politics, and a return to their properties and lives in Rome. Sertorius' war is, resultantly, seen as "an inheritance from the Sullan proscription",[96] and its end, along with his death, signalled the close of the civil wars started by Sulla's First March on Rome. None of the proscribed, including those who fought with Sertorius, are known to have received a pardon.[198] Ironically, the defeat of Sertorius (and thus the last Marian resistance) may have caused the repealing of several of Sulla's laws, as there was no longer "fear that the [Sullan] structure itself might crumble".[199] According to Steel, Sertorius' seizure of Hispania was "highly significant" as a display, similar to Sulla in his civil war, of how Roman foreign policy in the late second century relied greatly on domestic affairs.[59]

Spann believes that "Sertorius, if successful in Spain, clearly meant to invade Italy. He would not have set up some sort of independent state in Spain",[200] and so Gruen, "Sertorius' target was the government in Rome... of his political enemies. Had he been victorious, there would have been a change in leadership, not in social or political system".[201] Spann and Konrad view Sertorius' success in a march on Rome as unlikely;[202][203] however, Konrad believes existing discontent within the Sullan government "might have provided him [Sertorius] with enough support to mount a serious challenge to the regime once he crossed the Alps".[204]

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ c. 80–72 BC; https://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb417500287

- ^ Brennan 2000, p. 503 (arguing against 86 and earlier as well as 83 and later), 849 n. 242 (citing Konrad 1994, pp. 74–76).

- ^ Konrad 1987, p. 525, "That Sertorius always thought of himself and acted as a Roman proconsul... should no longer be doubted" (emphasis in original); Brennan 2000, p. 507, "Sertorius, the outlaw pro consule for Spain".

- ^ Brennan 2000, p. 502. "Sertorius' provincia was apparently Hispania Citerior, which he set out for... in late 83... [H]e may have been intended to hold both Citerior and Ulterior".

- ^ Broughton 1952, p. 70, placing promagistracy starting in 82 BC.

- ^ a b Konrad 2012.

- ^ Konrad 1995, pp. 160–62 (arguing for 73); Brennan 2000, pp. 508 ("Konrad['s case]... ultimately fails to convince"), 514 (placing assassination to 72), 852 n. 290.

- ^ Badian, Ernst (2012). "Perperna Veiento, Marcus". Oxford Classical Dictionary (4th ed.). doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.4876.

- ^ Konrad 1994, pp. 38–39; Spann 1987, p. 1. Nursia had received Roman citizenship in 268 BC.

- ^ Spann 1987, pp. 1–2. If Sertorius did have these ancestors, their names and deeds are not known.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 35 believes her name might have been Raia.

- ^ Plut. Sert., 2.1.

- ^ Spann 1987, pp. 4, 6.

- ^ Konrad 1994, xliii points out that although Cicero refers to the Sertorian War several times, "Cicero's reticence [about Sertorius himself] permits no guess as to how he felt about the man".

- ^ Cicero, Brutus, 180.

- ^ Spann 1987, p. 10.

- ^ Plut. Sert., 3.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 43.

- ^ Konrad 1994, pp. 46, 47.

- ^ Spann 1987, p. 16.

- ^ Spann 1987, p. 15; Plut. Sert., 3.2.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 48.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 47.

- ^ Spann 1987, p. 17.

- ^ Spann 1987, p. 18.

- ^ Spann 1987, pp. 18–19; Konrad 1994, pp. 48–49.

- ^ a b c Konrad 1994, p. 51.

- ^ a b c d Spann 1987, p. 20.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 95; Spann 1987, p. 20.

- ^ a b Konrad 1994, p. 137.

- ^ Spann 1987, pp. 21, 161.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 53.

- ^ Pina Polo & Díaz Fernández 2019, pp. 312–13. See also Plut. Sert., 4.1.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 54.

- ^ Sall. Hist., fragment 1.88.

- ^ Pina Polo & Díaz Fernández 2019, p. 313.

- ^ Spann 1987, pp. 21–22, 162.

- ^ Spann 1987, p. 22.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 56.

- ^ Plut. Sert., 8.

- ^ Plut. Sert., 4.

- ^ a b Spann 1987, p. 24.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 58. See also pp. 59–62 for argumentation that Sertorius served as plebeian tribune in 87 BC..

- ^ Spann 1987, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 63.

- ^ Spann 1987, p. 29.

- ^ a b Gruen 1995, p. 17.

- ^ Spann 1987, p. 30.

- ^ Plut. Sert., 5.3.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 69.

- ^ Spann 1987, p. 32.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 72.

- ^ Badian, Ernst (1962). "Waiting for Sulla". Journal of Roman Studies. 52: 47–61. doi:10.2307/297876. ISSN 1753-528X.

- ^ Konrad 1994, pp. 74–76.

- ^ Exsuperantius, De Marii, Lepidi, 43-44

- ^ a b Konrad 1994, p. 84.

- ^ Strisino 2002, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 82.

- ^ a b c d Steel, C. E. W. (2013). The end of the Roman Republic, 146 to 44 BC: conquest and crisis. The Edinburgh history of ancient Rome. Edinburgh, Scotland: Edinburgh University Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-7486-1945-0. OCLC 821697167.

- ^ Leach 1978, p. 25.

- ^ Konrad 1994, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Strisino 2002, p. 39.

- ^ Spann 1987, pp. 36–37, 151.

- ^ Exsuperantius, De Marii, Lepidi, 46-48

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 85.

- ^ Plut. Sert., 6.

- ^ Noguera, J; Valdés, P; Ble, E (2022). "New Perspectives on the Sertorian War in northeastern Hispania: archaeological surveys of the Roman camps of the lower River Ebro". Journal of Roman Archaeology. 35 (1): 22 – via Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 87.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 86.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 89.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 99.

- ^ Spann 1987, p. 44.

- ^ a b Orosius, Histories against the Pagans, Book 5, 21.3

- ^ Spann 1987, p. 45.

- ^ Konrad 1987, pp. 521–22.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 101.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 103.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 110.

- ^ Spann 1987, p. 51.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 112.

- ^ Sixty cubits is about ninety feet.

- ^ Plut. Sert., 9.

- ^ Spann 1987, p. 53.

- ^ Spann 1987, p. 54.

- ^ Plut. Sert., 22.6.

- ^ Konrad 1987, p. 526.

- ^ Spann 1987, pp. 58–62.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 116.

- ^ Spann 1987, p. 55; Plut. Sert., 22.

- ^ Konrad 1995, p. 126.

- ^ Broughton 1952, p. 80; Konrad 1994, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Broughton 1952, p. 81, citing Plut. Sert., 12.3, reporting title as propraetor.

- ^ Konrad 1995, p. 130.

- ^ Spann 1987, p. 57-58.

- ^ Konrad 1995, p. 130; Sall. Hist., 1.107.

- ^ a b c d Gruen 1995, p. 18.

- ^ Broughton 1952, p. 84 – citing Sall. Hist., 1.111M; Plut. Sert., 12.8 – reporting Marcus Calvinus' title as proconsul.

- ^ Leach 1978, p. 39; Plut. Pomp., 17.

- ^ Konrad 1994, pp. 50, 188.

- ^ a b Spann 1987, p. 63.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 188.

- ^ App. BCiv., 112.1.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2016, p. 160.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 124.

- ^ Plut. Sert., 11.2.

- ^ Spann 1987, p. 63; Plut. Sert., 11.

- ^ Konrad 1994, pp. 124–25.

- ^ Spann 1987, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Christian Müller in Hans Holbein the Younger: The Basel Years, 1515–1532, Christian Müller; Stephan Kemperdick; Maryan Ainsworth; et al, Munich: Prestel, 2006, ISBN 978-3-7913-3580-3, pp. 263–64.

- ^ Plut. Sert., 14.

- ^ Plut. Sert., 16.

- ^ Valerius Maximus, Memorable Deeds and Sayings, Book 7, 3.6

- ^ Noguera, Jaume; Valdés, Pau; Ble, Eduard (2022). "New perspectives on the Sertorian War in northeastern Hispania: archaeological surveys of the Roman camps of the lower River Ebro" (PDF). Journal of Roman Archaeology. 35 (1): 9, 22. doi:10.1017/S1047759422000010. ISSN 1047-7594.

- ^ Brennan 2000, pp. 425, 466.

- ^ Plut. Pomp, 17.

- ^ Plut. Sert, 15.1.

- ^ a b Livy, History of Rome, Book 91

- ^ Leach 1978, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Plut. Sert., 18.4.

- ^ Spann 1987, p. 91.

- ^ Leach 1978, p. 46.

- ^ Plut. Sert., 18.

- ^ App. BCiv., 108.1, though scholars doubt the figure of 300 specifically.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 185; Spann 1987, p. 87.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 185, who argues it was not a government in exile as Sertorius lacked the power of a consul to convene a Senate and only saw himself as a proconsul. Conversely; Spann 1987, pp. 88–89, who believes it was in fact a government in exile, and that the fact that it was a 'Senate' was manifest..

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 184; Spann 1987, pp. 86–89.

- ^ a b Brennan 2000, p. 503.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 185.

- ^ Spann 1987, pp. 89.

- ^ Plut Sert., 14.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 142; Spann 1987, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Leach 1978, p. 48.

- ^ Leach 1978, p. 47; Livy Per., 91.4.

- ^ Frontinus, 2.1.2 and 2.3.5.

- ^ Plut. Sert., 19.

- ^ Leach 1978, p. 49.

- ^ App. BCiv., 1.110.

- ^ Plut. Sert., 19.6.

- ^ Appian, The Mithridatic Wars, 68

- ^ Frontinus, 2.13.3.

- ^ a b Plut. Pomp., 19.

- ^ Livy Per., 92.

- ^ a b Plut. Sert., 21.

- ^ a b c Plut. Sert., 25.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2016, p. 168.

- ^ Brennan 2000, p. 406.

- ^ Plut. Sert., 22.1.

- ^ Konrad 1988, p. 253.

- ^ Konrad 1988, pp. 261, 259.

- ^ Leach 1978, p. 51.

- ^ App. BCiv., 1.113.

- ^ Plut. Sert., 10.

- ^ Konrad 1994, pp. 206–7. Konrad also argues that some of Sertorius' staff, particularly the distinguished officers Octavius Graecinus and Tarquitius Priscus, who had probably served under him since 82 BC, would not have joined in such a conspiracy to remove a relatively successful leader such as Sertorius unless his behaviour had become intolerable.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 205.

- ^ Plut. Pomp., 20.

- ^ a b c Plut. Sert., 26.

- ^ Konrad 1987, p. 522.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 215.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 211–212, 214; App. BCiv., 1.113.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 214.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 216.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 216; App. BCiv., 1.114.

- ^ a b App. BCiv., 1.114.

- ^ a b App. BCiv., 1.115.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 219.

- ^ Plut. Sert., 27.

- ^ Konrad 1988, p. 256.

- ^ Valerius Maximus, Memorable Deeds and Sayings, Book 7, 6e.3

- ^ Spann 1987, p. 137.

- ^ Florus, Epitome of Roman History, Book 2, 10.22

- ^ Pliny, Natural History, Book 7, 96

- ^ a b Caesar, Bellum Gallicum, 3.23.5.

- ^ Matyszak, p. 164.

- ^ Spann 1987, p. 140.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. lii.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2016, p. 169-170; Frontinus, 1.5.1, 1.10.1, 1.10.2, 1.11.13, 1.12.4, 2.3.11, 2.5.31, 2.7.5, 2.11.2, 2.13.3, 4.7.6.

- ^ Spann 1987, pp. 141–46.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 52.

- ^ Livy, History of Rome (Epitome), Book 96. Appian, Civil Wars, Book 1, 113. Florus, Epitome of Roman History, Book 2, 10.22.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. xlvii.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. lvi.

- ^ Valerius Maximus, Memorable Deeds and Sayings, Book 9, 15.3

- ^ Murphy, p. 1.

- ^ Plut. Sert., 1.

- ^ Gruen 1995, p. 381, in a passage rejecting the trope that homines militares such as Sertorius were unsuited to civil political life.

- ^ Spann 1987, p. 152.

- ^ "Scoprire Norcia: Le porte dell'antica cinta muraria". norciaintavola.it (in Italian). Retrieved 2024-07-28.

- ^ Spann 1987, p. 212.

- ^ Leach 1978, p. 210.

- ^ H.P. Collins, The Decline and Fall of Pompey the Great, p. 101

- ^ Goldsworthy 2016, p. 181.

- ^ Sall. Hist., 2.82.4.

- ^ Leach 1978, p. 45.

- ^ Spann 1987, p. 151.

- ^ Florus, Epitome, Book 2, 10.22

- ^ Plut. Sert., 22.

- ^ Katz 1983, p. 65.

- ^ Konrad 1988, pp. 257.

- ^ Gruen 1995, p. 27.

- ^ Spann 1987, pp. 213–14.

- ^ Gruen 1995, p. 413.

- ^ Spann 1987, pp. 147–48.

- ^ Konrad 1994, pp. 179–80.

- ^ Konrad 1994, p. 180.

Bibliography

[edit]Ancient sources

[edit]- Appian (1913) [2nd century AD]. Civil Wars. Loeb Classical Library. Translated by White, Horace – via LacusCurtius.

- Appian (2019) [2nd century AD]. "The Iberian book". Roman History. Loeb Classical Library. Translated by McGing, Brian C. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-99647-2.

- Cassius Dio (1914–27) [c. AD 230]. Roman History. Loeb Classical Library. Translated by Cary, Earnest – via LacusCurtius. Nine volumes.

- Livy (2003). Periochae. Translated by Lendering, Jona – via Livius.org.

- Plutarch (1917) [2nd century AD]. "Life of Pompey". Parallel Lives. Loeb Classical Library. Vol. 5. Translated by Perrin, Bernadotte. OCLC 40115288 – via LacusCurtius.

- Plutarch (1919) [2nd century AD]. "Life of Sertorius". Parallel Lives. Loeb Classical Library. Vol. 8. Translated by Perrin, Bernadotte. OCLC 40115288 – via LacusCurtius.

- Sallust (2015) [1st century BC]. "The Histories". Fragments of the Histories. Letters to Caesar. Loeb Classical Library. Translated by Ramsey, John T. ISBN 978-0-674-99686-1.

- Sextus Julius Frontinus. Stratagems. Translated by Thayer, Bill – via LacusCurtius.

Modern sources

[edit]- Brennan, T. Corey (2000). Praetorship in the Roman Republic. Oxford University Press. Two volumes (consecutively paginated).

- Broughton, Thomas Robert Shannon (1952). The magistrates of the Roman republic. Vol. 2. New York: American Philological Association.

- Gruen, Erich (1995). The last generation of the Roman republic. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02238-6.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2016) [2003]. In the Name of Rome: The Men Who Won the Roman Empire (1st Yale University Press ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-21852-7.

- Katz, B.R. (1983). "NOTES ON SERTORIUS". Rheinisches Museum für Philologie. 126 (1): 44–68. JSTOR 41245136.

- Katz, B.R. (1981). "Sertorius, Caesar, and Sallust" (PDF). Acta Antiqua Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 29: 285–313.

- Konrad, Christoph F (1987). "Some Friends of Sertorius". American Journal of Philology. 108 (3): 519–527. doi:10.2307/294677. ISSN 0002-9475. JSTOR 294677.

- Konrad, Christoph F (1988). "Metellus and the Head of Sertorius". Gerión Revista de Historia Antigua. 6 (253): 253–61.

- Konrad, Christoph F (1994). Plutarch's Sertorius: A Historical Commentary. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2139-X.

- Konrad, Christoph F (1995). "A new chronology of the Sertorian war". Athenaeum. 83. Pavia: 157–87.

- Konrad, Christoph F (2012). "Sertorius, Quintus, c. 126–73 BC". In Hornblower, Simon; et al. (eds.). Oxford Classical Dictionary (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.5852. ISBN 978-0-19-954556-8. OCLC 959667246.

- Leach, John (1978). Pompey the Great. London: Croom Helm.

- Matyszak, Philip (2013). Sertorius and the Struggle for Spain. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84884-787-3.

- Murphy, William J. (1973). Quintus Sertorius: the reluctant rebel (master's degree). Michigan State University. doi:10.25335/M5KH0F06S.

- Pina Polo, Francisco; Díaz Fernández, Alejandro (2019). The Quaestorship in the Roman Republic. De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110666410. ISBN 978-3-11-066641-0.

- Spann, Philip O. (1987). Quintus Sertorius and the Legacy of Sulla. Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 0-938626-64-7.

- Strisino, Juan (2002). "Sulla and Scipio 'not to be trusted' ? The Reasons why Sertorius captured Suessa Aurunca". Latomus. 61 (1): 33–40. JSTOR 41542385.

External links

[edit]- 120s BC births

- 70s BC deaths

- 2nd-century BC Romans

- 1st-century BC Romans

- Ancient assassinated people

- Ancient Roman exiles

- Roman Republican generals

- Assassinated military personnel

- Assassinated ancient Roman politicians

- People from Norcia

- Roman governors of Hispania

- Roman quaestors

- Roman Republican rebels

- Roman Republican praetors

- People of Sulla's civil war

- People of the Sertorian War

- People of the Mithridatic Wars